William Sanders: the first African American classical scholar

William Sanders Scarborough was born in Macon, Georgia, on February 16, 1852. He is widely considered to be the first African American Classical scholar.

Born to an enslaved mother and a free father, Scarborough and his family made their home alternately on the East and West banks of the Ocmulgee River before finally settling in East Macon where his parents lived out their lives. Because the law dictated that the children of enslaved mothers inherited their status, Scarborough was born enslaved, but enjoyed a great degree of freedom as his mother was allowed to live in her own house and his father was a free railway employee. This degree of freedom appears to have facilitated his ability to access an education as he learned to read.

Scarborugh attended Lewis High School and Macon, established in by the American missionary association to educate Black children. He furthered his education at Atlanta University (now Clark-Atlanta University) and continued to Oberlin College where he earned a degree in 1875.

Scarborough taught in several schools, including Lewis High school in Macon as well as Paine Institute in Cokesbury, South Carolina. Eventually, he became a professor at Wilberforce University and Wilberforce, Ohio. He he is perhaps best known for the textbook first lessons in Greek, which was published in 1881. He was the first African-American to join the modern language Association and the third to join the American theological association. Scarborough was a longtime member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

He passed away on September 9, 1926.

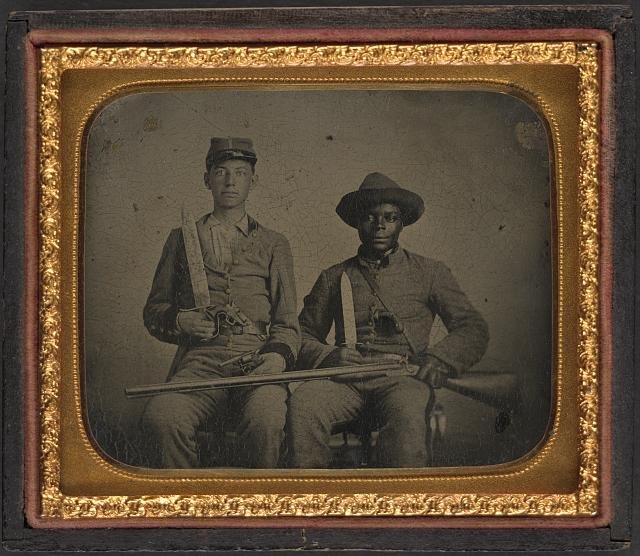

Makin’ a Myth: Charley Benger and the Myth of Black Confederates

Whether or not Black men served in the Confederate armed forces during the Civil War, as well as their roles, has been a subject of debate for decades. This debate recently emerged here in Macon, as a Civil War heritage group proposed donating a plaque to Macon-Bibb in honor of Charley (also referred to as Charles) Benger, a Black musician who played for the Confederate army during the Civil War. The plaque would’ve been installed in Rose Hill Cemetery. The heritage group, the local NAACP, and other Black leaders have been asked to meet to

What is known of Charley Benger’s life is documented in various primary resources, such as military records and newspapers. Collectively, they paint a complicated, and depending on the interpretation, sometimes contradictory portrait of who he was as a man.

According to Confederate military records, Charles Benger enlisted in the Confederacy on April 20, 1861, in Macon. He is listed as a musician. Records indicate that he was paid three times that year: June, August, and October. He was discharged on July 20, 1862.

What is missing from the current narrative is that Benger apparently re-enlisted on October 12, 1862 in Chatham County, Georgia.

A record of payment for Charley Benger. Note the remarks: “musician by consent of his master.”

US, Civil War Service Records available on fold3.com state that Benger was paid for September and October 1862 and joined as a musician “by consent of his master.” That notation contradicts the statement in Benger’s 1880 obituary in the Macon Telegraph (see below) that he was “never a slave,” suggesting that he was an enslaved person and served with the permission of his enslaver.

An article from the Macon Telegraph reporting the death of Charley Benger.

The Macon Telegraph article above also states that Benger “enjoyed a pension from his old company.” This claim is interesting and bears further investigation. According to the National Archives and Records Administration, Georgia began offering pensions to former Confederate soldiers who had lost a limb in 1877. As time passed, pensions were granted to additional groups. For example, other disabled veterans or their widows became eligible for pensions in 1879. It was not until 1894 that old age and other disabilities were considered, well after Charley Benger, who reportedly died of old age, passed away in 1880. A thorough search of Confederate pension applications did not reveal a pension application on Benger’s behalf, nor for this widow.

How can we understand this complex situation? Tune in to the latest episode of the Makin’ Black History podcast to learn more as we discuss this topic with Kevin Levin, author of Searching for Black Confederates: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth (University of North Carolina Press, 2019).

Profile: Dr. J. H. G. Williams

Physician and Surgeon

Graduate of Shaw University, Raleigh, NC

John Henry Giles (J.H.G.) Williams was born on September 7, 1872, in Anderson, SC to Coleman Williams and Alice Sherrard. He briefly attended Paine College in Augusta, but he had to delay his studies due to financial challenges. Williams furthered his education by attending Howard University before graduating in 1904 from Shaw University, a private historically Black college (HBCU) in Raleigh, NC. He began practicing medicine in Columbus, GA before relocating to Milledgeville, GA. where he practiced medicine and surgery. Williams married Minnie Maud Miller of Augusta on June 20, 1905, with whom he parented two children, John Henry Giles, Jr. and Grace Maud. Mrs. Minnie Maud Williams operated a private school for Black children at the site of the present-day Slater’s Funeral Home in Milledgeville. Dr. J.H.G. Williams later married Ella Alexander.

In Milledgeville, Dr. Williams operated a drug store and was a member of the C.M.E. Church, where he served as both a steward and a trustee. He later relocated to Macon, where he operated his business at 552 New Street and lived at 659 Spring Street. Williams was a neighbor of another prominent African American Maconite, Ruth Hartley Mosley. The site where his home was located is now a parking lot. He was a member of the Macon Academy of Medicine, which included other Black physicians, pharmacists, surgeons, and dentists. He died of a heart attack on April 4, 1930, and was interred at Oak Ridge Cemetery. Hutchings Funeral Home provided services.

What happened to the Williams Children?

Like many Southern African Americans, between 1910-1970, the Williams children left Georgia and participated in the Great Migration, a mass movement of African Americans from the Southern United States to northern, and western cities.

Both Williams’s children relocated to Washington, DC. Grace Maud Kelly (nee Williams) graduated from Howard University, and married Paul Kelly, who once published an entertainment newspaper in DC called “Nitelife.” She was a school teacher at Randall Junior High School, and a member of Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. She passed away in Washington, DC in 1961.

John Henry Giles Williams, Jr. also relocated to Washington, D.C., where he worked at the Social Security Administration, among other occupations He died on May 10, 1988.

Emancipation Day: A Brief History

To many, January 1 is celebrated as #newyearsday2024 , but in the African American community this day is also known as #EmancipationDay, as it marks the effective date of the Emancipation Proclamation, the 1863 document that freed all enslaved people in states that were still in rebellion against the United States in the Civil War.

Macon was no exception to this tradition. A perusal of local newspapers reveals that the celebration was a popular one for the local African American community. Emancipation Day Celebrations were held at locations ranging from the City Auditorium to local churches like A.M.E. church on Cotton Avenue, to the City Auditorium. The programs featured music, prayer, and readings, such as renditions of the Emancipation Proclamation, and culminated with an address, usually by an esteemed member of. the community or a special out-of-town guests. In 1899, the guest speaker was none other than Booker T. Washington, the famed leader of Tuskegee Institute, now Tuskegee University.

Parades were also popular. In 1909, the Douglass Emancipation Society used the occasion to collect funds for a library. Military companies such as the Bibb County Blues, the Lincoln Light Guard, and Sandy Lockhart’s group, as well as schools, and other societies, participated in the parades.

Makin’ An Impression: Sara Frances Mitchell

Depending on your generation, you may have never heard of Sara Frances Mitchell. Although scholars of African American history have recognized her involvement in Malcolm X’s Organization for Afro American Unity (OAAU), many people in her hometown, particularly newcomers or those born more recently, are unfamiliar with her life and work and its connection to Macon.

Born in 1934 to Henry Huey Mitchell, Sr., and Eddie Mae Mitchell (nee Greene), Sara grew up in the Fort Hill Community. She attended Ballard Hudson High School and went on to attend Knoxville College, a private liberal arts Historically Black College University (HBCU) located in Knoxville, TN. Growing up, Sara was known throughout the city for her beautiful soprano singing voice. Sometimes she was accompanied on the piano by her older sister, Shirley, and occassionally Shirley and Sara were joined by their younger sister, Ann, appearing as the Mitchell Sisters. According to the Macon Telegraph, Sara delivered a moving rendition of “I Want Jesus to Walk With Me” at a meeting at Greater Allen Chapel AME Church during the 1962 Macon bus boycott.

Sara Frances Mitchell is pictured here, third from the left. Undated photo courtesy of the McCrorey family.

While working at the New Yorker magazine, Mitchell became acquainted with Malcolm X. He was so impressed with her that he invited her to an upcoming rally sponsored by his new organization, the Organization for Afro-American Unity (OAAU). He encouraged her to listen to the organization’s message and to write a critique, showing how the organization could improve its message. Impressively, she responded with a 21-page document, outlining her points. Today, the document is included in the Malcolm X papers, which are housed at the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research for Research in Black Culture, where she is credited as being a major contributor to the collection. Mitchell became a charter member of the OAAU along with fellow Maconite and Harlem Renaissance writer, John Oliver Killens.

A photo of Sara Frances Mitchell sitting next to Dr. Betty Shabazz, the widow of Malcolm X when she was crowned Miss African during Harlem’s annual Marcus Garvey Day (c. 1966 -photo courtesy of Ann McCrorey)

In 1966, she was crowned “Miss Africa” during Harlem’s annual Marcus Garvey Day Celebration. Eventually, she returned to the middle Georgia area, where she enriched the lives of young people in Crisp, Peach, Bibb, Twiggs, and Peach counties as an educator. Shepherd of Black Sheep, which recalls the assassination of Malcolm X, was published in 1981.

Sara Frances Mitchell passed away on October 7, 2017, and was interred at Woodlawn Memorial Park in Macon, Georgia. She is fondly and dearly remembered by her family, friends, and community.

To learn more about Sara Frances Mitchell and her work with the OAAU see the following resources.

Felber, G. (2015). “Harlem is the Black World”: The Organization of Afro-American Unity at the Grassroots. The Journal of African American History, 100(2), 199–225. https://doi.org/10.5323/jafriamerhist.100.2.0199

Manion, J. L. (2016). Understanding Underlying Similarities in Civil Rights Philosophies: A Survey of the Memoirs of Coretta Scott King, Malcolm X, Anne Moody, John Howard Griffin, and Sara Mitchell Parsons.

Mitchell S. (1981). Shepherd of Black sheep : a commentary on the life of Malcolm X with an on the scene account of his assassination. Harriet Tubman Foundation.

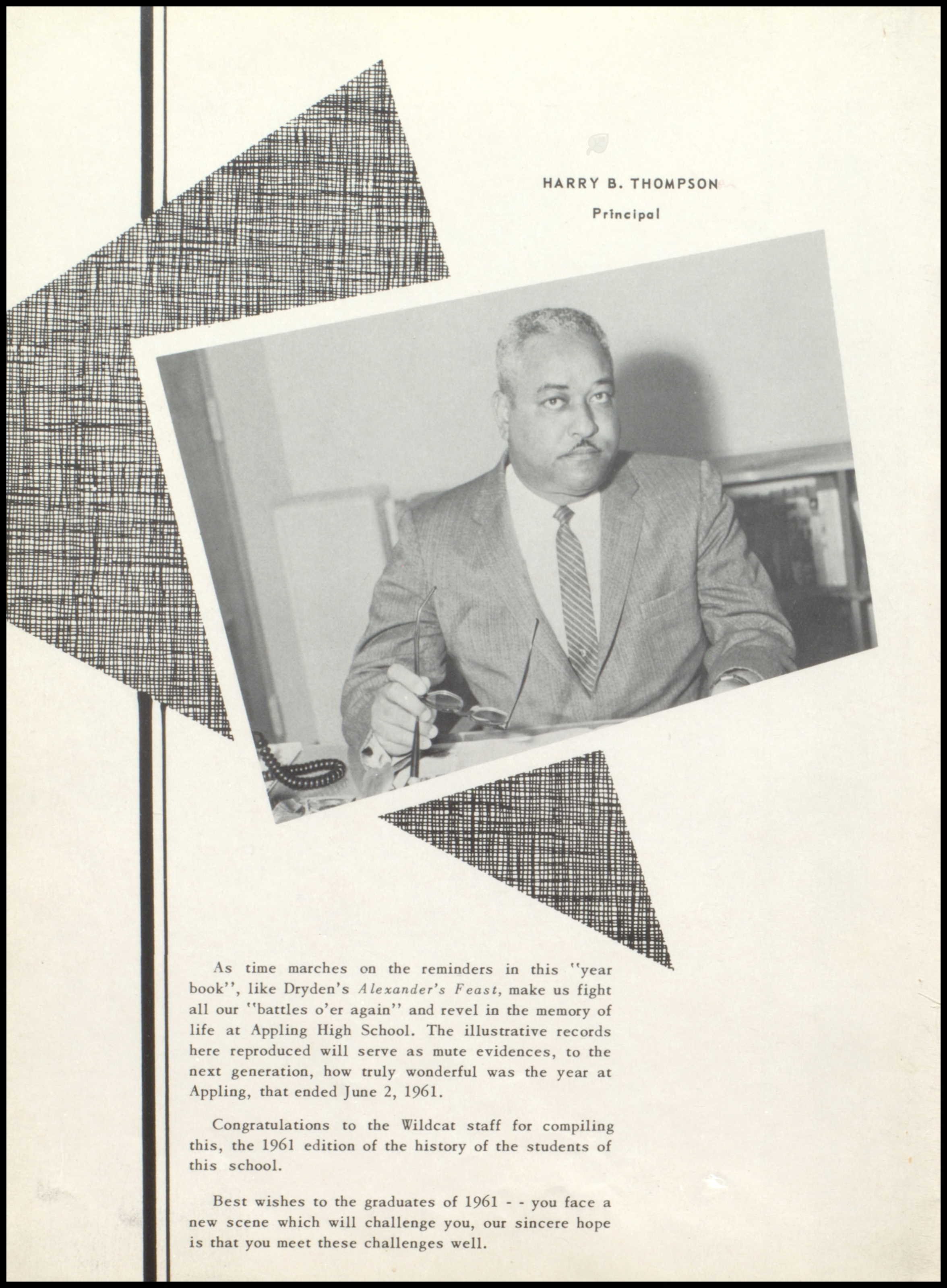

Harry B. Thompson: First Principal of Peter G. Appling High School

Every day, thousands of cars pass by the Harry B. Thompson Stadium located on Shurling Drive in Macon. Little do many know that the structure was named for the first principal of Macon’s second Black high school. Harry B. Thompson Stadium, which opened in 1996, sits on the former campus of Peter G. Appling High School, which opened in 1959. Prior to that date, the only option for Black youth to gain a high school education was at the co-educational Ballard-Hudson High School.

Ballard-Hudson has a storied existence in Macon’s history. Its roots can be traced to Lewis High School, an ambitious endeavor of the American Missionary Association, to provide education to newly emancipated African Americans following the Civil War. Although missionaries who arrived in Macon after the ward discovered rudimentary education already being provided by literate and semi-literate formerly enslaved men and women, Lewis is credited with being one of a handful of high school options, although private, for African Americans in the south. Lewis High School changed its name to Ballard Normal & Industrial Institute in 1888. It merged with Hudson High School, the first public high school for Black youth, in 1942.

Seventeen years later, “across the river,” Peter G. Appling High School opened its doors in 1959. The school’s mascot was the Wildcats and Harry B. Thomspon was its first and only principal. Thompson came over from Ballard-Hudson, where he had also coached. A giant of a man, Thompson was a native of Bluefield, W.V., and graduated from Morris Brown College in Atlanta, where he was reportedly a star athlete. Loved and respected by many, Thompson was a member of Washington Avenue Presbyterian Church, earned a master’s degree from Atlanta University, and was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc.

"Makin’ a Podcast”

Street scene. Macon, Georgia, July 1936.

Source: Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Street scene. Macon, Georgia, July 1936.

Source: Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Hi, I’m Shaundra a sixth-generation Maconite. Increasingly, I’ve become concerned about the preservation of African American history in our community. With a background in history, education, cultural heritage, and information, I’m uniquely positioned to use my knowledge, skills, and abilities to educate others about the valuable contributions African Americans have made to Macon’s footprint. I’ve used my abilities over the past 23 years outside of my community; now I want to use them at home. The Makin’ Black History Podcast will be the vehicle through which I will do that.

Makin’ Black History was born at the dress tail of my paternal great-grandmother, who raised me in every sense of the word. Born in rural Hancock County in 1902, she moved to Macon around 1930, following one of her uncles, who had also moved here and settled in Macon’s Pleasant Hill neighborhood. She also lived in Macon briefly as a young girl, attending the Green Street School before returning to live in Hancock, County. She and her husband, along with their three young children, made their home in Macon’s Unionville Community. When ‘urban renewal” came to Unionville in the 1970’s she relocated to East Macon, where I was born.

I spent my formative years with her, during which she shared many memories of family and community history. I went on to earn a bachelor of Arts degree in History from Spelman College, where I concentrated in African American and United States history. After undergrad, I matriculated at Clark-Atlanta University, where I obtained a Master of Science in Library and Information Studies. I also hold a PhD in Educational Leadership from Mercer University. Together with my vocation as an information professional for over 23 years, my education has uniquely equipped me to tell the story of African American Macon.

So, what can you expect from Makin’ Black History? For our initial season, we’re planning a series of “mini-seasons” focusing on community, faith, education, and change makers. For example, “Makin’ a Way Out of No Way” will highlight those individuals and groups who were not deterred by the limitations of segregation and went on to provide essential services and resources. “Makin’ a Joyful” noise will illuminate the rich African American faith traditions in the Macon community. “Makin’ Plays,” a mini-series on African American Macon’s contributions to sports.

Be sure to subscribe and stay tuned for our inaugural episode!